“How can I save what I have made?”, this is the question a young girl asked me in her school’s class recently. In the past hour she had created her own website. It was about her and the books that she loved. Standing in front of me with her hands clamped around the loan laptop, she wanted to know how she could save her website. Her protectiveness revealed that she did not do this because she wanted to show it off, but because she wanted to continue to build it at home.

Primary schools are not my day-to-day work environment. That day I participated in a voluntary event, organized by my work, which had the goal of making societal impact. Among the various available options, I had chosen to learn children in disadvantaged neighbourhoods about computer programming. One of these assignments was making a website.

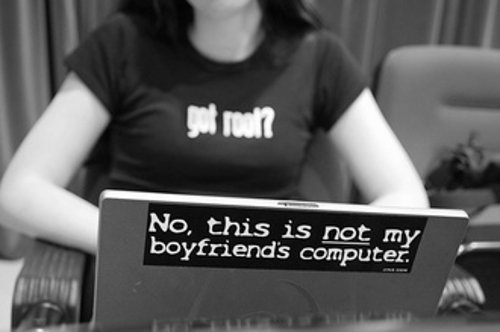

The girl that came to me with the question about how to save her website was one of a group of four that I was actively helping that day. All the girls in that small group were eager to learn, but she took the assignments quite seriously. She had the potential, the motivation and the attention span. This experience got me thinking: what would her chances be of actually making a career in IT?

There is a huge demand for skilled IT personnel in the Netherlands: forty-two percent of employers in IT struggles to find people, compared to only eighteen percent for general employment [1]. Given this demand, it should be easy for her to launch a career in IT, right?

Challenges

Many people want equal career opportunities for everyone, but the sad truth is that we do not live in a society that is meritocratic enough to meet that ideal. I see three major challenges for this girl: where she lives, the ethnical group she is part of and her gender.

Firstly, she lives in a disadvantaged neighbourhood. Sadly, the statistics about this are not at all uplifting [2]. Children that grow up in these neighbourhoods score lower on tests, experience more health problems and more psychological problems, and their poor socio-economic status tends to extend across generations. The only real exception to this is kids that have a resilient personality. The effects on them are smaller, but they also move out of such neighbourhoods much earlier in life [3, 4]. Nevertheless, even if she has a resilient personality, the fact remains that her neighbourhood provides less access to modern technology.

Secondly, even if she would go into IT and become, say, a software developer, she is part of an ethnic minority. The unfortunate fact is that minorities, also in the Netherlands, have a harder time finding a job and holding on to it: eight percent of highly educated minorities have no job, where this is only about three percent for the majority group: a telling sign. Even disregarding all this, the question remains: would she end up in IT at all?

The Gender Trap

When I was choosing a school to go to learn the craft of software development, in the late nineties, I attended various information events. I distinctly remember one such event. As almost everyone there, I too was accompanied by a parent: my mother. At the end of the presentation, she was the one parent in the room that dared ask the question: “are there any girls studying here?” The unsatisfying answer after a confused stare and some silence was: “no, there aren’t any, this is a technical school.”

This brings me to my third point: has that imbalance improved at all since that time? We would expect perhaps that half of the people working in IT is female, and the other half is male. However, that is not the case looking at present day workforce numbers. The country that seems to do this best is Australia with nearly three out of ten IT workers being female, whereas the Netherlands scores poorly with a score of only half that: less than two out of ten [5].

Is that due to a difference in capability? Are males ‘naturally’ better at these more technical subjects than females? There indeed is a bit of a developmental difference between boys and girls, but it may not be what you think.

Let’s take the most abstract subject as example: math. It may appear that boys are better at math, but that is not really true. Averaging out over their entire childhood into adolescence: boys and girls really are equally good at math. However, girls tend to develop language skills faster and earlier. Since boys lag behind in that development, it appears that they are better at math. Don’t be fooled by this deception: girls are not worse at math, they are better at language [6].

This difference between the genders disappears throughout adolescence, but by that time, paths have already been chosen. This is a sad consequence of our education systems pressuring children to make life affecting choices early on, which is not helped by reinforced stereotypes through gender specific toys and activities.

Parents

This brings me to another question: to what extent can parents influence their children? Specifically, can average parents, by parenting, influence their children’s personality and intelligence? How much do you think that influence is? Think about it for a minute.

This may come as a shock, but the effect of parents on their children’s personality and intelligence does not exist. To better understand this: consider that if anything parents do affect their children in any systematic way, then children growing up with the same parents will turn out to be more similar than children growing up with different parents, and that is simply not the case [7].

So, what does influence a child’s personality and intelligence? Half of that is genes, the other half is experiences that are unique to them. Those experiences are shaped largely by their peers. To some extent we all already know this: whether adolescents smoke, get into problem with the law, or commit serious crimes depends far more on what their peers do, then on what their parents do [8].

Don’t misunderstand me. Parents can inflict serious harm on their children in myriad ways, leaving scars for a lifetime, but that’s not what the average parent does. On the flip side, parents can also provide their children with the opportunity to acquire skills and knowledge, for example through reading, by playing a musical instrument or even encouraging them to explore computer programming. Hence, they can influence the conditions for them to get the right kinds of unique experiences.

Conclusion

Despite the odds being stacked against the girl that asked me how she could save her website. Looking backwards, why was that volunteering day so important? Was I really there to teach her how to do computer programming? No, not really, I was there to provide her with a unique experience that is rare to have in her regular day-to-day environment. It is my hope that his has cemented a positive association with IT in her, which may just tip the balance the right way.

As a final word I think that these kinds of volunteering efforts are important. Whether you work in IT or elsewhere, please consider giving others unique inspirational experiences to save, cherish and build upon. Because despite her odds, what she experienced may in the end actually make the difference for both her and her friends.

Sources

- Kalkhoven, F. (2018). ICT Beroepen Factsheet.

- Broeke, A. ten (2010). Opgroeien in een slechte wijk.

- Mayer & Jencks (1989). Growing Up in Poor Neigborhoods.

- Achterhuis, J. (2015). Jongeren in Achterstandswijk.

- Honeypot (2018). Women in Tech Index 2018.

- Oakley, B. (2018). Make your Daughter Practice Math.

- Turkenheimer, E. (2000). Three Laws of Behavior Genetics and What They Mean.

- Pinker, S. (2002). The Blank Slate.