If you do not sleep you will die within months. Though, it’s unlikely that you would voluntarily stay awake twenty four hours for days at a time, modern society with its many distractions, makes it tempting to trade a little bit of sleep for a little bit of something else every day. Is this a wise trade-off to make? To answer that question: let’s dive deeper into sleep.

Rhythm

A decade ago I visited the music festival Sziget in Budapest. I camped there with a group of friends near the northern tip of the ‘party island’. After several days, thanks to a combination of staying up very late and sleeping with an eye mask and earplugs, my usual waking time had settled around noon. Despite the intense heat buildup in my tent during the morning hours, I still had an actual, though shifted, sleep rhythm. Where does this rhythm come from?

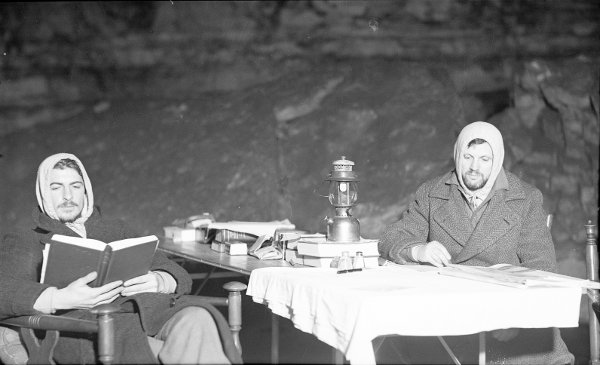

Living for several days on a music festival terrain, while an unforgettable experience in many ways, was not very convenient. Nevertheless, this inconvenience does not remotely come close to that of living in a cave without exposure to daylight for a month. This is what the father of modern sleep research, Nathaniel Kleitman, did in 1938 together with one of his students. Experimenting on himself was not new to Kleitman, as he also kept himself awake on benzedrine for up to hundred-eighty hours at a time just to measure the effect [2]. Little did he know that a form of this would later become a popular party drug at festivals for staying awake and boosting energy: speed.

Back to Kleitman’s cave experiment: it revealed two important things. Firstly, if there is no sunlight, our bodies can still self regulate sleep and wakefulness. Secondly, our sleep cycle is not exactly twenty four hours, but a little bit longer. This observation gave rise to the concept of what we nowadays call rhythm of approximately (circa) a day (dian): the circadian rhythm.

The presence of sunlight resets the rhythm, and keeps it from shifting. This is quite similar to the way that your computer, whose clock is not entirely accurate and suffers from drift, synchronizes its time at regular intervals by contacting computers with more accurate clocks using the Network Time Protocol. Indeed, some alarm clocks are equipped with radio signal based synchronization which essentially does the same thing.

Pressure

The first few days at the Sziget festival, when my rhythm had not shifted as much yet, I felt very sleepy near the end of the day when I stayed up late. But I noticed that when I stayed up long enough, there was a moment, usually in the early morning, where I got over the sleepiness and started feeling more alert again. Since my rhythm had not shifted yet: what caused this?

Besides the circadian rhythm our bodies have an other mechanism to regulate sleep. As long as you are awake your sleep pressure rises through the buildup of the neurochemical adenosine in your brain. The higher the sleep pressure, the more you actually feel like sleeping. This pressure is referred to as the sleep drive, whereas the circadian rhythm is called the wake drive.

If you were ever in a lecture where another student fell asleep on their desk with a loud thud you know what high sleep pressure can do: it will make you nid-nod, falling in and out of slumber, even if you really want to consciously pay attention. While this is fairly harmless during a lecture it can be extremely dangerous in other situations, for example: when driving.

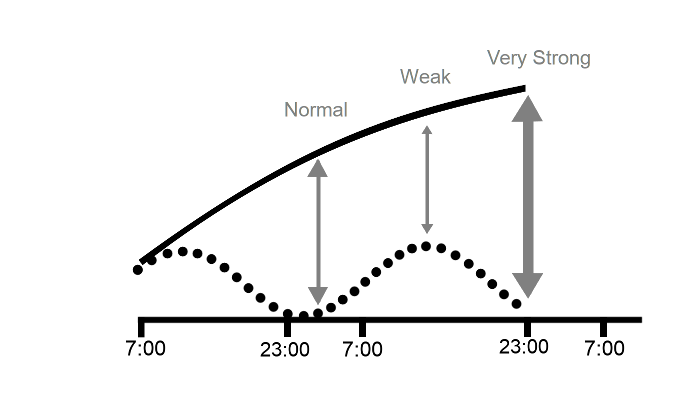

The interesting thing is that the circadian rhythm and sleep pressure are independent ‘systems’. As your sleep pressure continues to build up, your circadian rhythm may already be swinging back up, making you feel awake and more alert: exactly what I was experiencing the first couple of days at the festival. The figure above shows this: once you stay awake long enough the distance between the sleep pressure arc (top) and the circadian rhythm (bottom) becomes less, only to hit you much harder again as the circadian rhythm comes back down, resulting in a very strong urge to sleep.

Reset your brain

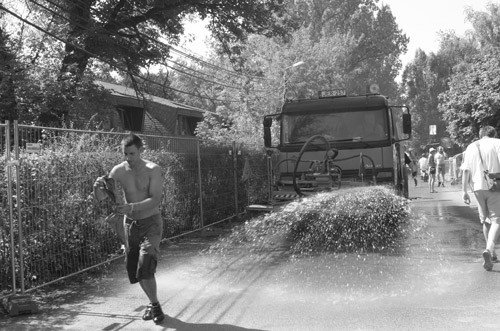

A good night consists of seven to nine hours of sleep opportunity, subtract from that half an hour to an hour to get the actual time slept. Back to the Sziget festival: not everyone had the fortune of being able to obtain a good night’s sleep. One evening we met a group of girls that had set up their tent next to the twenty-four hour DJ booth. I probably don’t need to tell you that setting up their tents there did not bode well for their sleep opportunity. Hence, we spent the night socializing with them. As we sat and talked on a set of wooden benches time flew by and before we knew it the sun came up again. The festival terrain was nearly silent, until we heard a loud rumbling sound.

It was around six in the morning, and the cleaning crew rolled in. A literal wall of people that moved from the front to the back of the festival terrain picking up garbage, followed by truck mounted water sprayers that cleaned the streets. An impressive sight.

In the deep stages of sleep something similar to what that cleaning crew did happens in your brain. Electrical waves sweep from the front to the back of your brain. This consolidates what you experienced and learned the previous day, and at the same time helps you prepare for sponging up new things the next day. In fact, not sleeping for one night reduces your ability to form new memories the next day by a whopping forty percent.

Better sleeping through chemistry?

Sitting on those benches at the festival, pulling an all-nighter, was not good for retention of memories, but also not good for overall wakefulness. The next day I had serious problems staying awake, thanks to the before mentioned buildup of sleep pressure. As a quick fix I turned to coffee: the stimulant of choice to keep one awake under such circumstances.

The caffeine in coffee blocks the binding of certain chemicals in the brain. This makes you feel more alert while your body is still tired. A negative effect is that once you do sleep after having coffee, you will have problems reaching the deep stages of sleep and thus will acquire less deep sleep overall. Ironically, this lack of deep sleep can trap you in a dependency cycle where you actually need coffee in the morning to feel refreshed after poor quality sleep.

It was a festival, so not only did we drink coffee. There was also plenty of cheap alcohol to go around. Beer, wine, shots, you name it, they had it. This stuff had the opposite effect of coffee: it made me feel sleepy. Alcohol, after all, is a depressant.

Alcohol makes you fall ‘asleep’ faster by sedating you, but as a side effect it heavily fragments your sleep. You wake up much more often than you usually would, though you do not consciously register this. This is the reason why the day after an evening of drinking a lot, you feel extremely drowsy. A secondary effect is that you do not reach the REM stage of sleep, which is vital for learning and memory formation. The debilitating effect of alcohol on memory formation is similar to that of not sleeping at all.

Consequences

Regardless of the cause: what else, besides memory and learning problems, really happens when you do not sleep enough? When I came back from the festival I had a throat infection. Not surprising: sleeping just one night for only four hours, instead of eight, reduces the presence of natural killer cells by over seventy percent. Doing this repeatedly left me much more vulnerable to infections, and there were plenty of germs floating around there. For such a short time, and the great fun I had there, that was an acceptable trade-off. However, that luxury of choice does not always apply to everyone. Involuntary chronic sleep deprivation incurs a heavy toll.

A chronic lack of sleep increases risk of physical diseases, like cancer, heart disease and diabetes, and also of mental diseases, including depression, anxiety and suicidality. Sleeping too little generally means that your life expectancy will go down dramatically. The evidence for this is strong enough that we know that if you were to actually sleep consistently for only 6.75 hours per night, you will likely live only into your early sixties.

Conclusion

What can you do to improve sleep? Three tips: firstly, maintain a regular schedule, which means: go to sleep and wake up at the same time every day, also during the weekends. Secondly, take care of your sleep ‘hygiene’: make sure your room is sufficiently dark and cool, around eighteen degrees Celsius, and avoid screens before you go to bed. Thirdly, avoid drinking coffee and alcohol, especially shortly before you go to bed, but also in the late afternoon and early evening.

Going to a music festival and losing some sleep by choice like I did is not a big deal. The real problem is that two thirds of all adults worldwide structurally fail to get the recommended minimum amount of sleep opportunity of seven to nine hours per night. Please, don’t be one of them. Sleeping is the single most important thing you can do to reset your brain and body health every day. Trading a little bit of sleep for a little bit of something else is not worth it in the end.

Sources

- Walker, M. (2017). Why We Sleep.

- Levine, J. (2016). Self-experimentation in Science.